Plagiarism Guide

What is Plagiarism? | Specific Examples | Penalties | Avoiding Plagiarism | Other Resources | Real-World Cases

1. What is plagiarism? Blatant vs. Inadvertent.

At the most basic level, plagiarism is presenting someone else’s work as your own. This definition, however, is not always useful in helping students and inexperienced writers distinguish when they are plagiarizing from when they are legitimately presenting information learned from a specific text.

Plagiarism is perhaps a greater potential pitfall in scientific writing than writing in the humanities and other disciplines. This is because scientific writing does not allow direct quotes from reference material. Everything must be paraphrased. This means that there is no margin for error in scientific writing.

When most students think of plagiarism, they think of the most blatant cases, cases in which someone downloads an article from the web or buys a pre-written essay from an online service and presents it as their own. These are very serious offenses and they do occur. Usually it is not difficult to detect when this has been done. Students at the W have been caught doing this and they were expelled from the university.

These blatant cases, however, are relatively rare. The most common form of plagiarism, both at the W and at universities across the country, is what we might call inadvertent plagiarism. These are cases where the student plagiarizes but the student is not entirely aware that what they have done is plagiarism. Often students doing this have some inkling they are skirting on the edge of propriety, but they convince themselves they haven’t really crossed the line because they don’t know how to do a better job. This kind of inadvertent plagiarism is most often due to the student’s lack of experience in scientific writing and their lack of clear understanding as to what exactly does and does not constitute plagiarism.

In a typical case, the student plagiarizes from a large number of sources. The student has done a significant amount of research and has taken notes from a nicely diverse group of books and articles. But when it comes time to write their essay or assignment, large numbers of the phrases come directly from the sources the student has consulted. The student doesn’t recreate just a single source word-for-word, as they would in a case of blatant plagiarism; instead the student is trying to do the right thing by using information from a variety of sources. Unfortunately, in the end, the essay or assignment contains strings of phrases taken directly from the sources used — a phrase from one source, followed by another phrase from a second source, followed by a phrase taken from a third source, etc. In many cases, the student will scrupulously cite all the sources for their phrases. The student is not really intending to plagiarize and is trying to follow acceptable writing and citing procedure. But, if the phrases closely resemble (they don’t even have to be identical) those of the original source, it is still considered a form of plagiarism, even if the sources have been cited! The penalties for plagiarism still apply, even if it was inadvertent plagiarism.

Good intentions are not enough to avoid charges of plagiarism and the subsequent penalties. All that matters is the final result. It must be free of all forms of plagiarism, blatant or inadvertent.

The student cannot resort to the expedient of just putting quotes around the phrases taken from their sources, because direct quotes are generally not allowed or used in scientific writing. There are exceptions. For instance, in Dr. Oppenheimer’s MA 111/112 writing assignments, direct quotes are permitted with proper citations. However, unless you are explicitly told otherwise by the instructor, assume that direct quotes are not permitted in any science or math writing you are assigned.

2. Specific examples of plagiarism.

In scientific writing, you generally don’t plagiarize information (especially if you have cited the source), you plagiarize how that information is presented. Here, with examples, are some of the ways students commonly plagiarize scientific writing. All the examples will use as their starting point the same text:

By lining up chimp chromosome 22 and human chromosome 21 and comparing them nucleotide by nucleotide, the consortium found instances in which one nucleotide was substituted for another in only about 1.44% of the sequence. The chimpanzee chromosome has been sequenced to an accuracy of less than one error in 104 bases, so sequencing mistakes account for less than 1% of the observed single-nucleotide mismatches. There is also an impressive number (68,000) of small to large stretches of DNA that have been either gained or lost (these are called insertions or deletions, indels for short) in one species or the other.

Source: J. Weissenbach. 2004. Nature vol. 429 27 May 2004, pp 353-355.

Example 1 – Complete plagiarism despite citation

Comparing the genomes of humans to chimpanzees has yielded key insights into the evolutionary relationships between the two species. Some of these insights come from aligning individual chromosomes from the two species and looking for both similarities and differences. For instance, when the sequence of chimp chromosome 22 is compared to its human counterpart more than 98.5% of the sequence is chimp chromosome has been conserved in its human counterpart, but differences at the nucleotide level do exist. The chimpanzee chromosome has been sequenced to an accuracy of less than one error in 104 bases, so sequencing mistakes account for less than 1% of the observed single-nucleotide mismatches (Weissenbach, 2004.) One of the ultimate goals of these comparison efforts is to determine which of the sequence differences between chimps and humans account for their different traits.

NOTE: Copying even a single sentence word-for-word is considered plagiarism even if the surrounding sentences are different and even if the copied sentence cites the source.

Example 2 – Still plagiarism despite changing a few words

Comparing the genomes of humans to chimpanzees has yielded key insights into the evolutionary relationships between the two species. Some of these insights come from aligning individual chromosomes from the two species and looking for both similarities and differences. For instance, when the sequence of chimp chromosome 22 is compared to its human counterpart more than 98.5% of the sequence is chimp chromosome has been conserved in its human counterpart, but differences at the nucleotide level do exist. The chimpanzee chromosome has been sequenced with an error rate of less than one error in 104 bases, so errors in the actual sequence-gathering process account for less than 1% of the observed single-nucleotide mismatches (Weissenbach, 2004.) One of the ultimate goals of these comparison efforts is to determine which of the sequence differences between chimps and humans account for their different traits.

NOTE: Taking the author’s original sentence and changing a few words but leaving large parts of the original sentence’s words and structure intact is still considered plagiarism, even if the slightly re-written sentence cites the source.

Example 3 – Avoiding plagiarism

Comparing the genomes of humans to chimpanzees has yielded key insights into the evolutionary relationships between the two species. Some of these insights come from aligning individual chromosomes from the two species and looking for both similarities and differences. For instance, when the sequence of chimp chromosome 22 is compared to its human counterpart more than 98.5% of the sequence is chimp chromosome has been conserved in its human counterpart, but differences at the nucleotide level do exist.

Chromosome 22 of the chimpanzee has had its sequence determined with an error rate lower than one in 10,000 nucleotides, so errors in the actual sequence-gathering process are responsible for no more than 1% of the individual nucleotide differences that have been found between humans and chimps. (Weissenbach, 2004.) One of the ultimate goals of these comparison efforts is to determine which of the sequence differences between chimps and humans account for their different traits.

All the words from the original sentence have been changed. However, it is true that the essential structure of the sentence – what information is presented in what order – has been retained. This is not a problem as long as you are limiting the structural similarities to one sentence. If there were many sentences in a row taken from an original source, with their wording changed but the essential sentence structure unaltered, you are in danger of committing structural plagiarism (which we will define below) despite the efforts to reword the material.

In the first two examples, the writer is guilty of some degree of plagiarism because they have relied on the original author to express the ideas for them.

In the case of students writing essays, reports, and assignments for class, two of the most important things the instructor is looking to grade the student on are:

- Did the student do a good job researching the topic; and

- Was the student able to show an understanding of the details of the topic?

If the student has constructed a piece of writing by pasting in other authors’ sentences with appropriate citations, the student is demonstrating that they successfully accomplished 1. They did a good job of researching the topic and finding information from a variety of (cited) sources.

But the student is not demonstrating 2, an understanding of the material, and the student’s mark will suffer accordingly. Unless the student puts the information from their sources in their own words, the instructor has no way of knowing if the student really understood what they were reading. All the writing demonstrates is that the original authors understood the topic. Did the student understand the topic? The instructor can’t tell one way or another.

If you understand a topic, you are able to articulate your understanding in your own words. You need to do this in your writing if you want full marks and if you want to avoid charges of plagiarism.

3. What are the penalties for plagiarism at The W?

At the W, any work an instructor has deemed to be plagiarism is given an automatic zero by university policy. In addition the student’s Dept Chair, Dean, and the Vice President for Academic Affairs’ office is notified of the offense. The Vice President for Academic Affairs (VPAA) keeps a file on all students who have committed acts of academic dishonesty, including acts of plagiarism.

If the plagiarism is a first offense, the matter is noted in the student’s file and no further action is taken. If there are previous offenses of any kind that have occurred during the student’s time at the W (they need not have occurred in the same class, the same semester, or same year), the student must appear before the university’s Academic Standards Committee. The committee has the power to impose additional punishments on the students beyond those already imposed by the instructor(s) who first reported the academic dishonesty. These additional punishments can include failing the course, suspension, or expulsion from the university. The committee is not required to impose these additional punishments – they can choose to do nothing beyond what the instructor deemed appropriate – but they do have the power if they feel the case warrants them.

More ambiguous acts of plagiarism, that might arise out of a misunderstanding of what exactly constitutes plagiarism (for instance, copying a sentence word-for-word, but then citing its source) might be met with less severe penalties, at least on the first offense. Or they might be punished equally harshly. It is up to the Committee. Of course, repeated offenses of even the most borderline cases of plagiarism will be met with increasingly harsh punishments. You can only claim ignorance for so long.

If a particular first act of academic dishonesty is considered sufficiently blatant and egregious, the VPAA can convene the Committee without waiting for a second offense.

You can read the University policy on plagiarism here.

4. How do you avoid even inadvertent plagiarism?

Here is an excerpt from Voet & Voet, 2004. Biochemistry 3rd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p 35. It is titled, Reading A Research Article.

Research reports more or less all have the same five-part format. They usually have a short abstract or summary located before (or, in some journals, after) the main body of the paper. The paper then continues (or begins) with an introduction, which often contains a short synopsis of the field, the motivation for the research reported, and a preview of its conclusions. The next section contains a description of the methods used to obtain the experimental data. This is followed by a presentation of the results of the investigation. Finally, there is a discussion section wherein the conclusions of the investigation are set forth and placed in the context of other work in the field. Most of the articles are full papers, which may be tens of pages long. However, many journals also contain communications, which are usually only a page or two in length and are often published more quickly than are full papers.

It is by no means obvious how to read a scientific paper. Perhaps the worst way to do so is to read it from beginning to end as if it were some kind of a short story. In fact, most practicing scientists only occasionally read a research article in its entirety. It simply takes too long and is rarely productive. Rather, they scan selected parts of a paper and only dig deeper if it appears that to do so will be profitable. The following paragraph describes a reasonably efficient scheme for reading scientific papers. This should be an active process in which the reader is constantly evaluating what is being read and relating it to his/her previous knowledge. Moreover, the reader should maintain a healthy skepticism since there is a reasonable probability that any paper, particularly in its interpretation of experimental data and in its speculations, may be erroneous.

If the title of a paper indicates that it may be of interest, then this should be confirmed by a reading of its abstract. For many papers, even those containing useful information, it is unnecessary to read further. If you choose to continue, it is probably best to do so by scanning the introduction so as to obtain an overview of the work reported. At this point most experienced scientists scan the conclusions section of the paper to gain a better understanding of what was found. If further effort seems warranted, they scan the results section to ascertain whether the experimental data support the conclusions. The methods sections is usually not read in detail because it is often written in a condensed form that is only fully interpretable by an expert in the field. However, for such experts, the methods section may be the most valuable part of the paper. At this point, what to read next, if anything, is largely dictated by the remaining points of confusion. In many cases this confusion can only be eliminated by reading some of the references given in the paper. At any rate, unless you plan to repeat or extend some of the work described, it is rarely necessary to read an article in detail. To do so in a critical manner, you will find, takes several hours for a paper of even moderate size.

Copyright © 2004 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The following passage is what might result from an inexperienced researcher who writes while reading the original or who uses notes that copy out word-for-word large chunks of the original text. This passage is not taken verbatim from the original, but it is nonetheless an example of plagiarism. There are some phrases and word choices that were lifted from the original. These have been bolded:

Articles from most biological journals typically follow a standard format. They are prefaced with an abstract summarizing the article. The article proper begins with an introduction giving the background information that lead to the current study. The introduction usually ends with a preview of the article’s main conclusions. The introduction is followed by the methods section of the article. This is a detailed description of the methodology used to obtain the experimental data. Next comes the actual results and findings of the experiments are described. Finally, a discussion section reveals what the researchers have concluded from their studies and attempts to fit those conclusions in with other work in the field.

The worst way to attempt to read a journal article is from beginning to end. Instead, the reader should take a selective approach and dig deeply into the article only when it appears that meaningful information will result. The reader need only begin the article if it has an interesting title and abstract. Scanning the introduction will provide an overview of the work as a whole. Turning next to conclusions at the end of the discussion section will reveal what the researchers believe they actually found as a result of their work. If further information is desired, the results section can provide information about the experimental support for these conclusions. The methods section often does not need to be read except by experts interested in the picayune experimental details of the research. What remaining parts of the article need be read in any greater detail depends of what aspects of the preceding reading left questions in the reader’s mind. Papers need be read in their detailed entirety only infrequently (Voet & Voet, 2004.)

There is a significant, but not overwhelming, number of word choices and phrases lifted from the original. But even if these were eliminated and other constructions were substituted, the passage as it stands would still constitute plagiarism. It is too close to the source to be considered an original work by the author. It makes all the same points in the same order using several of the same expressions and phrases. There is nothing in this passage that is not in the original.

Citing the source does not change this. Citing a source does not lift the obligation on a writer to produce original work.

A better strategy would be to take notes that are as skeletal and as schematic as possible.

- Avoid words whenever possible in your notes and you run less risk of plagiarizing phrases and word choices from the original.

- Avoid structuring your notes in a sequential manner and you run less risk of plagiarizing the structure of the original.

- Group related material together in your notes regardless of how the material was sequenced in the original.

- Break up the sequence as much as possible so you will have a hard time recreating the original’s structure from the structure of your skeletal notes.

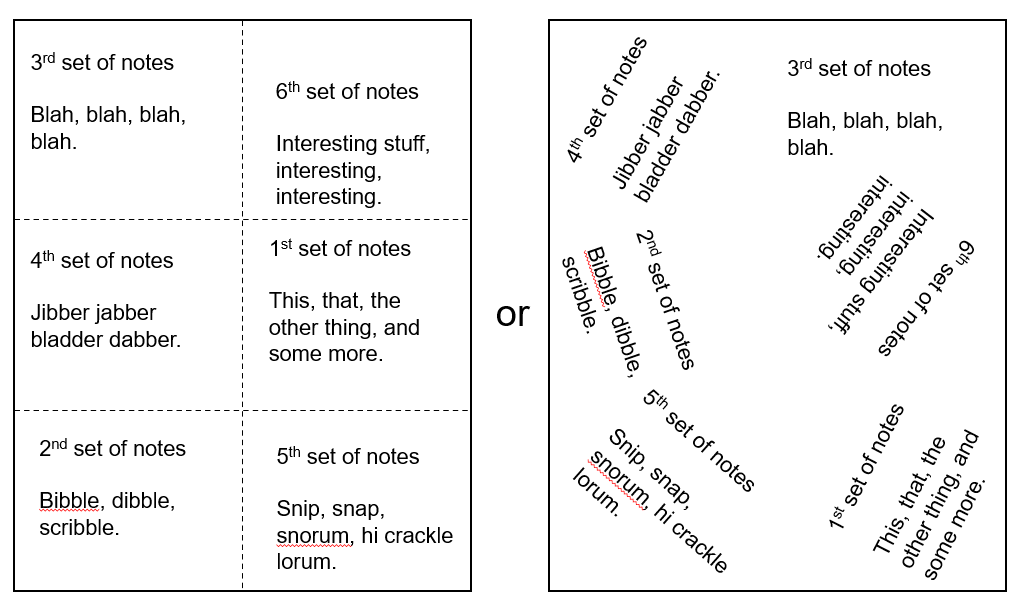

Skeletal, fragmented notes taken from the original passage might look like this:

Attempting to write a passage from skeletal notes such as these will avoid recreating the structure and reusing the phrases of the original, because neither of those things is present in your notes, and you won’t remember the original structure or phrases when you finally sit down to write up your notes. These kinds of notes force you to create your own phrases and structure, because they don’t provide the original as an irresistible model to follow.

The hardest thing to do when taking skeletal notes is to avoid recreating the structure of the original source. Everyone has the tendency to write down information in their notes in the order they encounter it. Then, when writing up your own essay, it becomes very easy to just re-write the information in your notes in the same order. Even if you’ve taken pains to put all the information in your own words, you have still recreated the structure of the original and you lay yourself open to charges of plagiarism.

When taking skeletal notes, try to get out of the habit of writing down on the page and putting your notes in the same order in which you encounter them. You can try dividing your paper into different sections and randomly choosing a different section on a completely different part of your page every time you write something new down. You can try rotating your paper in different random directions every time you have something new to write down. Just make an effort to scramble the order of the information so that when you write up your notes you are forced to come up with a new order and structure that doesn’t plagiarize the original’s.

5. Other plagiarism resources.

Other resources on plagiarism, how to recognize it, and how to avoid it are listed below:

- Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, B.C., has a useful web-based tutorial — including quizzes — on plagiarism, how to recognize it, and how to avoid it.

- The Chronicle of Higher Education published several articles in their 17 Dec 2004 issue on plagiarism and several specific plagiarism cases. A good place to start is their article titled Everybody’s Talking About Plagiarism. The article provides links to their related articles. (Requires subscription to access.)

- Georgetown University has a good discussion, with examples, of plagiarism.

- Dartmouth University has a detailed discussion of how and when to properly cite sources.

- If you google plagiarism these days, you will provided with literally hundreds of links to sites dealing with various aspects of the issue.

6. Real-world cases of plagiarism.

Plagiarism is not limited to students. Here are some links to articles describing various authors, academics, journalists, and scientists recently accused of plagiarism.

Dr. Paul McCrory, a neurologist at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience & Mental Health in Melbourne, Australia, was accused in 2022 of more than twenty incidences of plagiarism in his writings for scientific publications. Dr. McCrory was prominent in international groups developing treatments and protocols for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain injury associated with professional sports like football and boxing. (Dr. McCrory was generally dismissive of the threat of CTE to most athletes.) Here is a link to a site that found ten incidences of plagiarism in Dr. McCrory’s professional writing. Six of the ten incidences in that article were self-plagiarism, where Dr. McCrory simply re-used text he had published previously elsewhere. This was nonetheless still considered professional misconduct. In 2022, Dr. McCrory resigned in disgrace as head of the Concussions in Sports Group (CISG). That same year, the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM), where McCrory had been editor-in-chief until 2008, retracted nine articles McCrory had authored because of incidences of plagiarism, including self-plagiarism. The BJSM also added “expressions of concern” to 38 other articles McCrory had published there, indicating suspicions about the quality of the content in those articles. Dr. McCrory is no longer treated as an expert in CTE by journalists or professional sports organizations.

In 2019, the Crime Junkie, a true-crime podcast centering on a new crime each episode and consistently one of the top 10 podcasts in the Apple podcast charts, was accused of plagiarizing material in several of its episodes The most serious accusation was that a March 2019 episode on the murder in Arkansas of a teenager named Kacie Woody had relied without any attribution on material from reporter Cathy Frye who had written about the crime for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette when it had originally happened in 2003. Frye accused the podcast of using wording from her original articles almost verbatim. Other writers also accused the podcast of plagiarizing their true-crime reporting in podcast episodes. The host of the Crime Junkies podcast, Ashley Flowers, temporarily took down five episodes of the podcast and later re-uploaded them with citations to their original sources included on the web notes for each episode.

Dr. Matthew C. Whitaker, Associate Professor of History at Arizona State University, was accused in 2011 and again in 2015 of plagiarizing the sources for books of popular history he had written. Dr. Whitaker had inserted paragraphs from his sources with only a few words changed, and even though he often, but not always, cited those sources, he was accused of taking the work of others. A side-by-side comparison of some of the material he had plagiarized is available here (limited free articles from the linked site; then a paywall applies.) Dr. Whitaker was forced to resign from all his positions at the University effective May 2017.

In July 2009, a research article was retracted by the journal that published it because it contained two paragraphs plagiarized word-for-word from an earlier review article on the same topic, written by someone else. There were no complaints about the science in the paper, conducted by a research group lead by Professor Karim Nayernia at Newcastle University (Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK). The paper dealt with creating sperm cells from human embryonic stem cells and was originally published in the journal Stem Cells and Development. This was the first report of developing functional sperm cells from human stem cells and represents a significant development in stem cell technology, if the results hold up, but the editors at Stem Cells and Development considered the plagiarism in the introductory material transgression enough to retract the entire paper. Professor Nayernia claims he mistakenly sent the journal an early draft of the paper and that the final draft would have removed the plagiarism.

Kaavya Viswanathan was a Harvard University undergraduate who, when she was just 17 years old, was signed to a $500,000 contract to write two young-adult novels. Her first book was published in Spring 2006 and a Hollywood studio bought the rights to turn it into a movie. In April 2006 The Harvard Crimson published a story accusing Viswanathan of plagiarizing two books of another young-adult author, Megen F. McCarthy. Eventually, at least 14 passages similar in phrasing and structure to McCarthy’s writing were discovered in Viswanathan’s novel. Passages similar to works by other authors were also discovered. Wikipedia has the complete list of suspect passages. Viswanathan’s novel was withdrawn by the publisher and the plans to make a movie version were halted. Despite the close similarities to other authors’ works, Visawanathan said the copying was unintentional and unconscious. Harvard university declined to get involved in the case, saying the plagiarism was non-academic and is not covered by Harvard’s code of conduct for students. She continued as a student there and graduated with honors in 2008. After Harvard, she attended law school at Georgetown University and is now a practicing immigration attorney.

Plagiarism of entire scientific articles is not all that common, but it does happen. Yung Park, a materials scientist at the University of Cambridge in England, is accused of copying other scientists’ journal articles from 1997 to 2001 and submitting them as his own research. Park was asked to leave Cambridge. The journals which published his papers have added notes to their archives indicating that the papers contain plagiarized material and in some cases have entirely removed the articles from their archives.

Written by: Ross Whitwam

Last updated: 5 Nov 2022